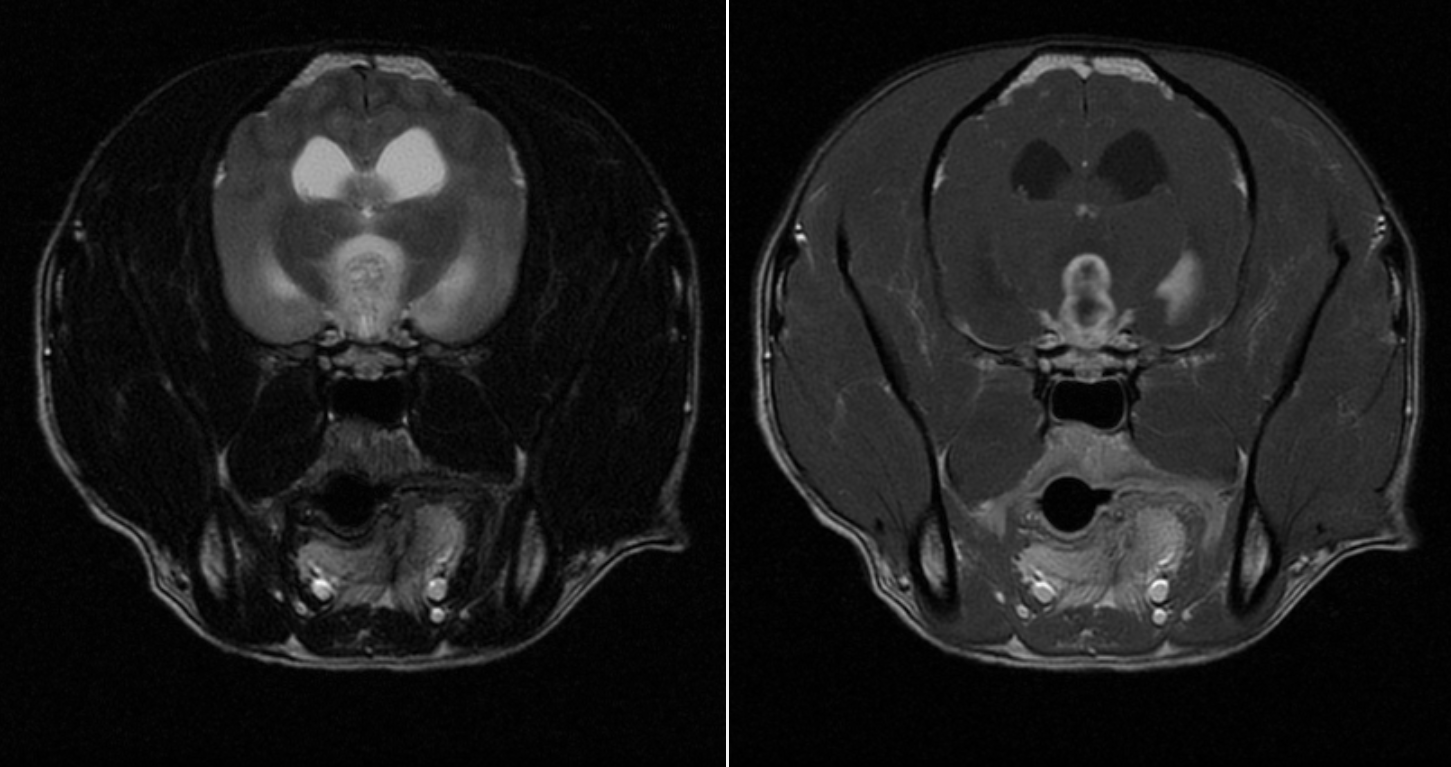

When he started getting older (around 13), our Boston Terrier, Jack started peeing in the house. At first we thought it was just his old age. But eventually we discovered that he had an advancing brain tumor (cystic meningioma) which was gradually reducing his mobility. Eventually, couldn’t move without great pain, so he was going in the house to avoid having to walk outside.

To treat Jack’s brain tumor, we were prescribed Prednisone, a steroid drug used by both people and pets. The drug literally saved his life and continued to keep him healthy after radiotherapy. But there is definitely a catch to Prednisone: A huge increase in the number of times your dog will have to pee each day. We were totally unprepared.

Held hostage by pee

After going on Prednisone, Jack was peeing once every waking hour — on the carpet, in his bed, in his crate, and everywhere in between. At night it was slightly better … he had to go once every couple of hours. But that made for some pretty sleepless nights.

And the constant deluge of bodily fluids made for many loads of laundry and mad dashes to clean up pee on the floor. No one really told us about the frequent potty breaks we were in for due to the drug side effects. The good news is that the pee breaks are manageable once you figure everything out, as there are many products out there that can help. Below you’ll find several tips on how to deal with the constant flow of pee that you might have to deal with older dogs or dogs on Prednisone.

Tips and products for dealing with older dogs that pee in the house / urinate frequently

1. Pee pads / puppy pads are your best friends

When you have an older dog or one on Prednisone that has to pee all the time, you don’t want to ruin your nice carpet, rug, bed, or car seat. To protect your stuff, you’ll want to buy pee pads, and lots of them. There are two main types: reusable cloth and disposable paper puppy pads.

Reusable pee pads

The cloth puppy pads are a lot nicer than the disposable ones. They typically absorb more liquid, tend stay in place better, and contain splashing more effectively. On Amazon, you can buy reusable puppy pee pads designed for pet use, which tend to be square and can have fun, pet-themed designs. Another option is to buy mattress pad protectors for people, which usually have a more plain design and come in a wider variety of (often larger) shapes, which makes them more ideal for use in a bed, on a sofa, or in the back seat of a car, for example.

But if you’re thinking you want to only use reusable pee pads, know that it will take at least a few hours to turn cloth pee pads around after they’re soiled, and you probably don’t want to feel chained to the washing machine all day — that gets old very quickly!

Disposable pee pads

No matter how many reusable pee pads you have, you will want disposable puppy pads as a backup, especially for dogs on Prednisone — you’re going to be dealing with a large volume of pee! Also, f you ever travel with your dog and won’t have easy access to a washing machine, disposable pee pads are lifesavers. Amazon sells 100 pee pads for about 18 dollars.

As mentioned before, disposable puppy pads aren’t as good as the cloth ones, but there are products that help you deal with some of the of the weaknesses of disposables. For example, a waterproof silicon tray for puppy pads can help you contain some of the splashing issues you might experience with thin pads, and it can help your disposable pee pads stay put better too, they like to slide around if stepped on fly away if there is any wind.

Pee pad best practices

One strategy that will help you keep your sanity is to use multiple layers of pee pads stacked on top of each other. Some dog owners put many disposables on top of each other, or place reusable pads one underneath disposable ones. That way, when you can peel off the top layer and you’ll already have a backup in place.

While Jack was going through radiation therapy, he was weak and sometimes unable to control himself at all, which made for many accidents. We ended up making a giant rug out of disposable pee pads to protect the hotel carpet (pictured above), with some reusable ones strategically scattered about. Eventually things got better, as Jack regained his strength, and we provided him with better pee options / trained him on where to go.

2. Build your own grass pee area: Sod or Astroturf

If you live in a house or apartment without easy access to the outside, you might want to build your own little lawn / doggie pee area in the corner of living room or out on the porch. Our living area is on the 3rd floor, so getting outside can be a bit of a trek, so we came up with two solutions using real sod and artificial grass.

Real grass dog potty

We decided to put a little bit of natural greenery on the balcony so Jack can just step outside quickly to do his business. Now instead of having to carry him down flights of stairs for a quick pee, we just have to open the door and he’s standing on actual grass that he can potty on. Sod is great at absorbing liquids and smells. It’s also pretty easy to clean if Jack decides to poop on it — we just use a doggy bag to pick it up as if we were outside.

To set up a real grass doggie pee area, we simply purchased a tough, flexible car trunk liner to protect our wooden deck from the moisture and dirt of the sod and to contain pee. If you have a metal dog crate, you might already have a plastic tray that might also work —although these might be smaller and more shallow depending on the size of your crate.

You can head to your local landscaping store or garden store and pick up a few pieces of sod, but your should call ahead to make sure it’s available. Home Depot and Lowes occasionally have sod, but usually only in the warmer months. In Austin, we go to a place called King Ranch Turfgrass where 24″ by 18″ pieces cost about $2-$3 each. A larger 24″ x 48″ roll of sod goes for about $7. You’ll need to buy sod once a month, as eventually the grass dies and starts to stink. To fill the 40″ rectangular trunk liner we use with grass, you’ll need 3 piece of smaller sod or one larger roll.

Know that you won’t be the only dog owner to do this. The folks at the landscaping company I shop at told me that many people buy a few pieces of grass to put out on the porch for their dog. There are a couple of companies that will ship you grass in the mail, but it’s many times more expensive ($20 for a small piece) and you have to pay for shipping. But if money is no object, this might be a convenient option for you.

Fake grass

If it’s not convenient for you to buy real grass, you can order artificial grass online. Fake grass reduces splashing very well and it never dies or goes brown. The type of Astroturf we bought allows liquids to drain through very easily, which you want if you want your pee area to continue be odor free. A permeable turf also allows you hose it down from time to time for cleaning.

In general, Jack prefers the real grass, but we have the artificial grass pad inside too for times when it’s raining or too cold to go outside. To protect the wood floor underneath, we put disposable pee pads underneath.

3. Doggie door for a sliding door

If you have an older dog that needs to pee all the time, taking him or her out all the time can be a chore, or perhaps impossible when you have to go to work. Therefore, a dog door that your pet can pass through whenever they need to can be extremely handy, and it can help you avoid accidents that involve your dog peeing inside the house.

But a traditional dog door you install in a wall or door doesn’t work in every house. I live in a multi-level condo where the only practical place for a dog door is through a sliding glass door leading out to the balcony where we have a patch of real grass.

After a bit of research, we discovered an easy-to-install dog door insert that works with a sliding patio door system … no hole cutting required. This professional-looking dog patio door includes a clear glass panel and comes in multiple colors, so it matches with your existing door when installed.

Now all of our pets can go outside out whenever they want, but we had to train them to use the door first. For Jack, we stood on the opposite side of the closed dog door, then tempted him to step through using treats. We first held the door flap up for him, but over time let the door contact his body more and more so he could understand that he could push the opaque plastic flap open on his own.

The only challenge with this dog patio door is that it needs to be properly sealed if you want to keep the outside air from getting in. For this, you’ll need some good weather stripping tape. I bought four rolls of the rubber foam linked above to form a double seal on both sides of the product.

4. Doggie diapers and belly bands

At times after Jack’s radiation, we felt like we were hostages to dog pee. Especially when we were away from home, we were always nervous that Jack was going to pee indoors at someone else’s home, in the hotel, or in their office (we take him to work sometimes).

Now we use belly bands, which are essentially highly-effective fabric diapers made of an athletic material. They look like tuxedo cummerbunds or utility belts that wrap around Jack’s waist and penis (they only work for boy dogs). The belly bands help contain even large amounts of pee thanks to an absorbent fabric.

Belly bands are awesome and can take away a lot of the stress that comes from wondering whether you’re going to find a wet surprise in the corner. But you should know that once your dog pees in either a belly band or a dog diaper, you’ll want to change them. It’s not good for your dog’s skin to be in contact with pee for extended periods of time, as there is the possibility of infections or burns (from acidic urine) if that area stays wet for too long.

We ended up buying 15 belly bands (they come in packs of 3) because we like them a lot. Also, we didn’t want to have enough so we could use them every day without being chained to the washing machine all day, every day — it takes a while to dry them because they were designed to soak up and retain water.

When he had less control over his bladder, Jack could go through 5 of these a day. Now that Jack has more control and is trained to go in a designated peeing area, we only use belly bands on longer car trips, or when he goes to the office with us.

Since he’s a 20-pound Boston Terrier, the medium belly band fits Jack well. Also, the black model blends in with his fur, so that’s our favorite color. There are a wide variety of options and sizes available for all dogs though, and some of the choices are quite colorful if you want to make a fashion statement. For bigger dogs with a larger bladder capacity, some dog owners insert either Maxi pads or incontinence pads to absorb any extra liquids. However, a 20-pound dog like Jack doesn’t necessarily need the extra material.

Note: Belly bands work for male dogs only. Because of differences in anatomy, female dogs will have to use doggie diapers.

5. Doggie monitor / surveillance camera

One final product that has been super helpful for keeping an eye on Jack has been a wireless surveillance camera, which allows us to check in on him from a smartphone. When we leave the house, we can see how he’s doing from anywhere, which gives us peace of mind.

We really like the a product called the Wyze Cam, because it allows us to review a couple of weeks of recorded footage for free. Many wireless cameras (such as the Nest camera) charge a recurring monthly fee you want to be able to record and play back video. With the Wyze Cam, all you need is an inexpensive MicroSD card to enable the same feature.

Also, the Wyze Cam allows you to record timelapse video. Above, you’ll find a sample timelapse video that was useful for showing the vet how Jack’s head was bobbing his head back and forth over time, before his brain tumor diagnosis.

The best part of the Wyze Cam is that it only costs about $25. Plus, the Wyze Cam app is pretty intuitive, and you can view and save videos using any mobile device that runs iOS or Android.